The Puzzlingly Strong US

Why the US is not entering recession, despite monetary tightening and bank fragility

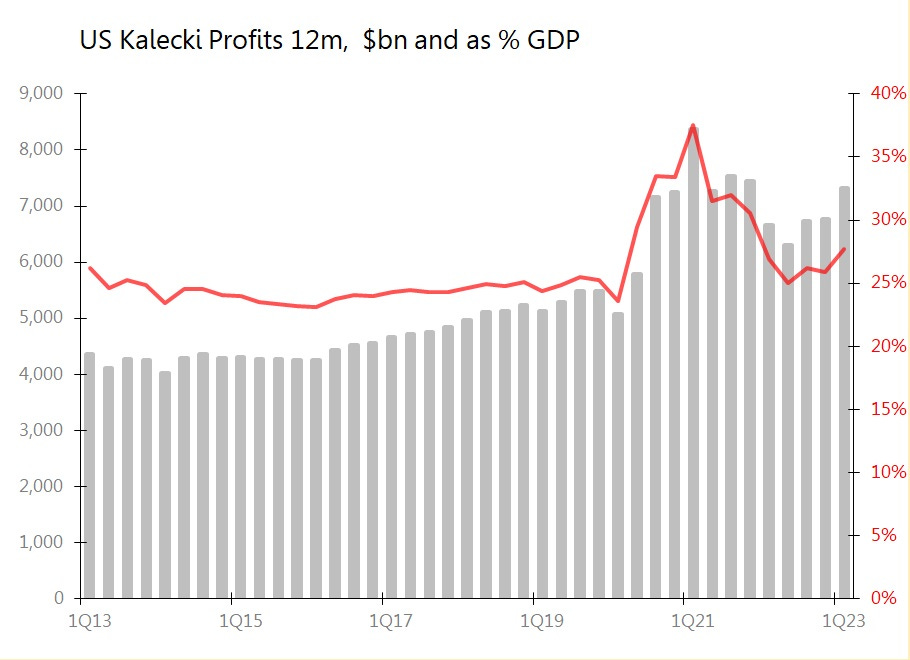

Whilst Kalecki profits are surging in the US, thanks mainly to a once-again bulging fiscal deficit, an industrial downturn threatening to turn into an industrial recession has been visible since the second half of last year. What’s more, the tightening of monetary conditions has put sufficient pressures on the banking system to generate significant bank failures and a dumping of their bond holdings. But these have not yet prompted a fall in bank lending (loans were up 9% yoy in April).

So what prevails? Profits growth?

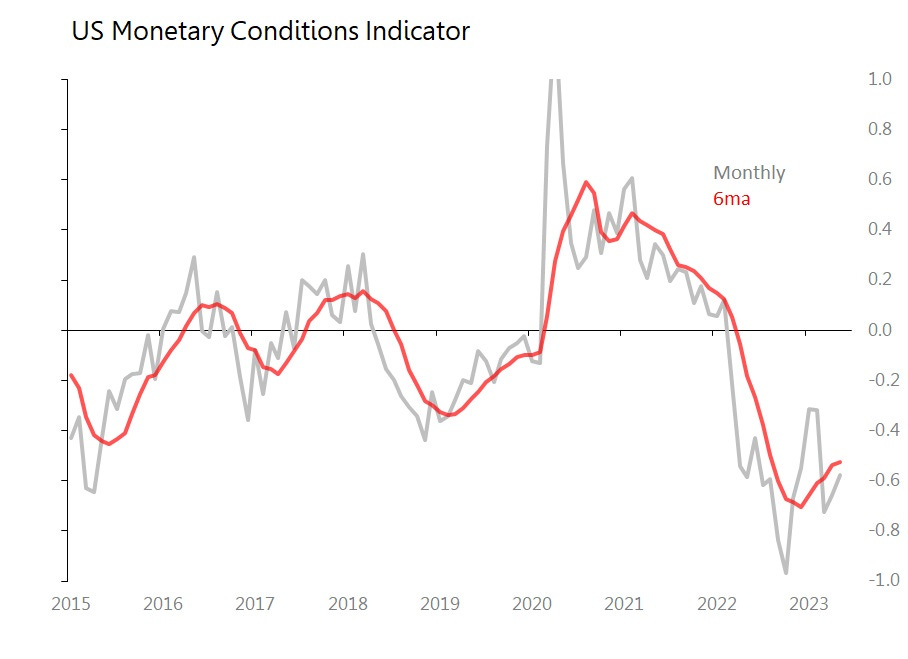

Or monetary conditions?

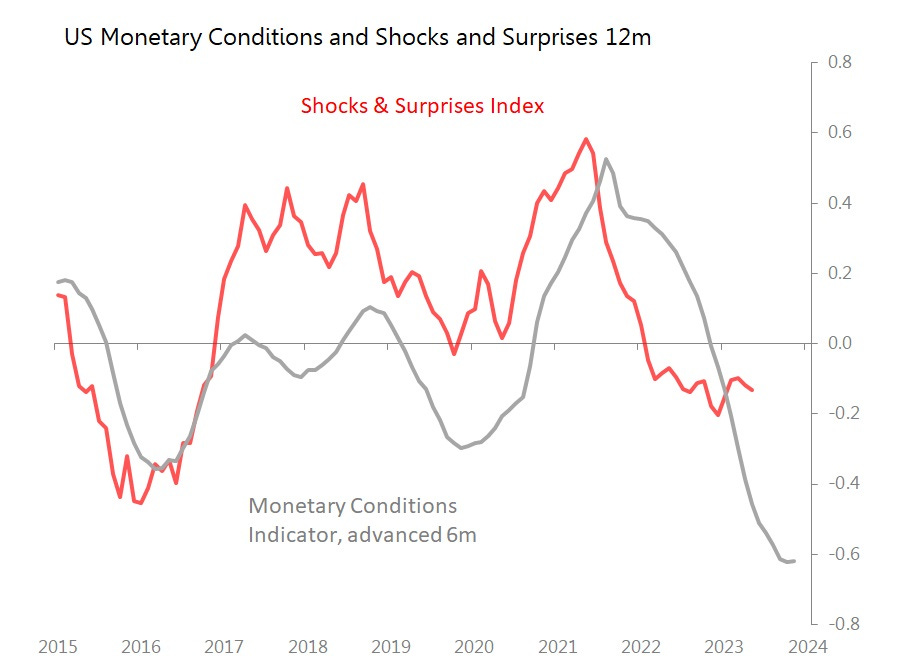

Historically, monetary conditions have broadly set the direction with which the US economy surprises or disappoints consensus, with those economic responses surfacing with a lag of approximately six months. And broadly speaking, that relationship seems to be holding true. If so, we should expect the second half of the year to be disappointing. . . .

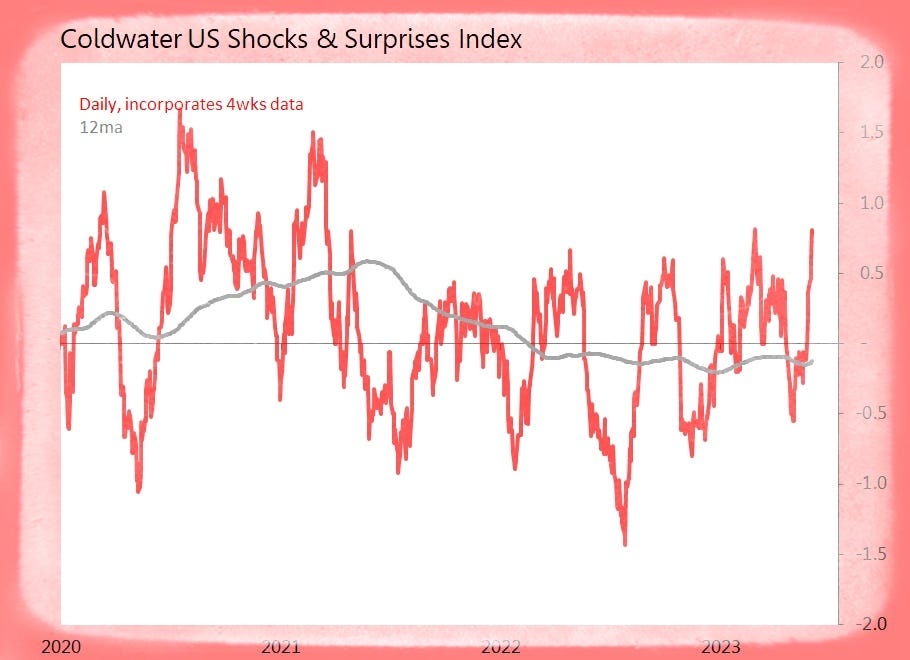

. . . . but the run of US data so far this year is tilting towards surprise, not shock. That suggests we are about to see a breakdown in the alliance between monetary conditions and the 12m shocks & surprises trend. What’s more, my favourite early recession warning flag - a collapse in heavy truck sales - is firmly Not Raised. No recession, then?

The forces of expansion and recession, then, look too finely balanced to allow any great degree of certainty about even the short-term outlook. A failure of economics, and a failure of this economist.

When faced with puzzles like this, sometimes breaking down economic conditions to produce proxies allowing a sort of Dupont analysis on a macro-basis can help.

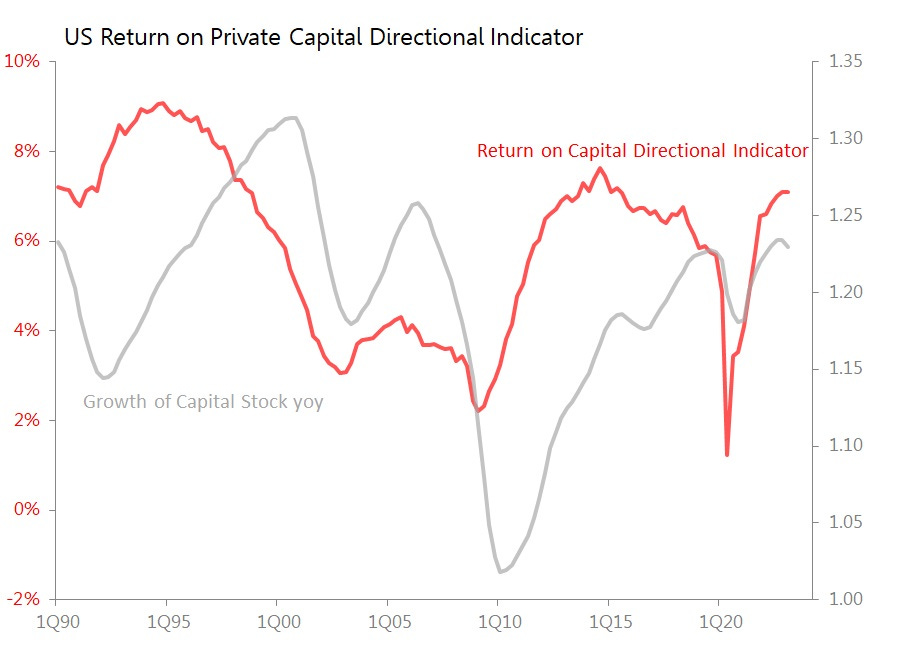

The first proxy to watch is the proxy for asset turns - in this case tracking final spending on domestic product as an income from an estimated stock of fixed capital. However, as I pointed out in ‘Recession Watch -Investment’ this ratio too puts the US economy on a knife-edge between recession and expansion: “by 1Q, however, the ROCDI has seemingly topped out, and investment spending is slowing. The overall level of ROCDI remains at historically high levels, so gives not compelling reason to expect a sustained investment slowdown.”

In other words, the current position is encouraging, but may be inflecting down.

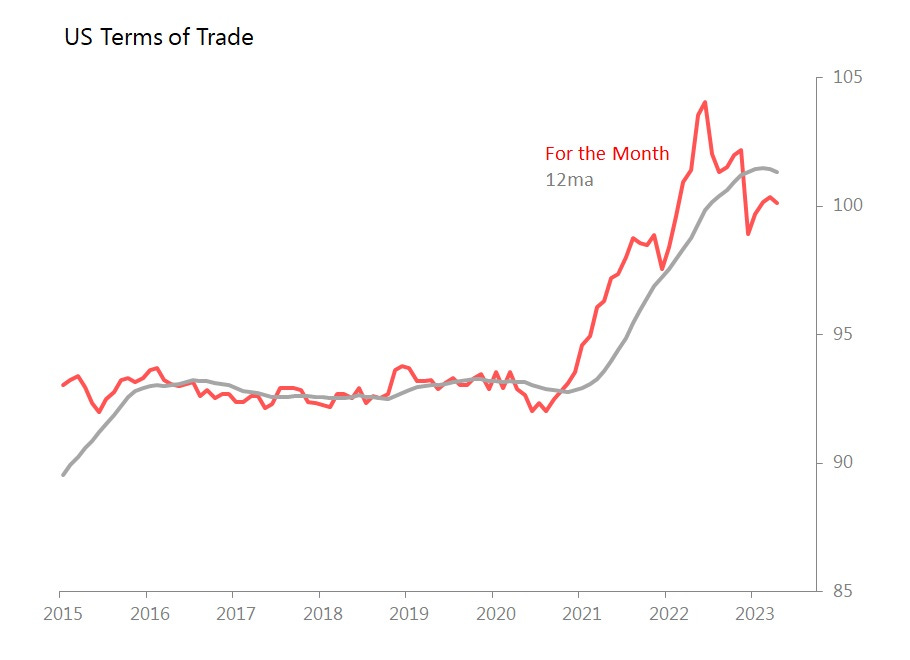

Next let’s look at a margins proxy - in this case, changes in the international terms of trade. The conclusion is similar: the last two years have delivered a historically very sharp improvement in US terms of trade, which will have helped cashflows and profits. As with the overall return on capital directional indicator, the US terms of trade are in a historically favourable situation, but the peak has passed and term of trade are now in decline. But only slowly, and from a very encouraging starting position. Jury still out.

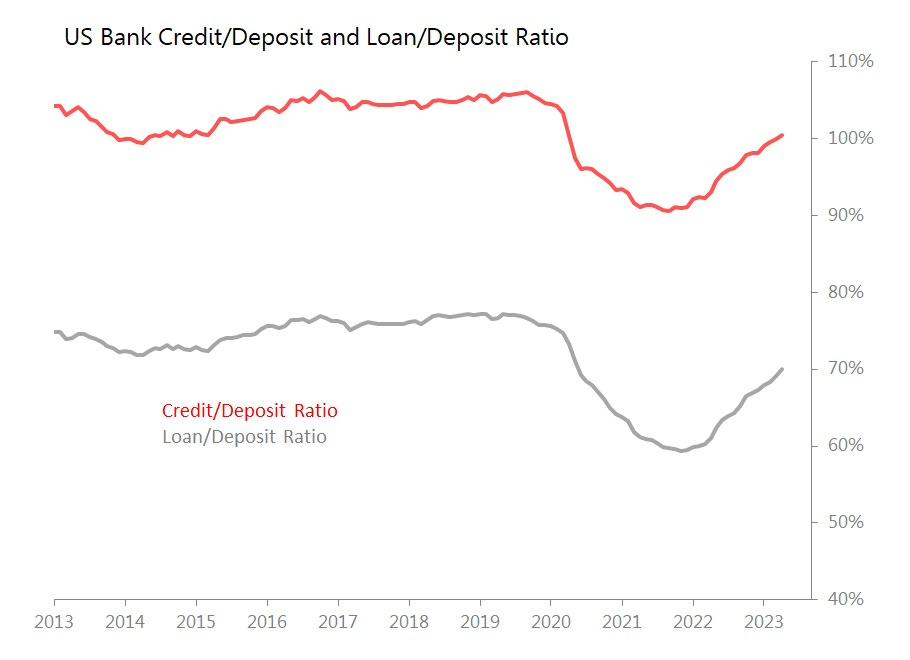

So let’s look at leverage: is the US economy being forced to deleverage? And the surprising, genuinely counter-intuitive news is that far from being forced to deleverage, the US banking system is actually re-leveraging the economy. Since the middle of last year, banks’ loan/deposit ratio has risen from 63%^ in June 2022 to 70% in April 2023. The overall credit/deposit ratio has risen from 94% to 100% in the same period.

Since we know that during the same period, deposits have been fleeing US banks, this is a profoundly unexpected result. But here are the fact: since May last year, the banking system has lost $760bn worth of deposits, but overall bank credit has risen by $318bn, with a $860bn rise in loans offsetting the $542bn fall in securities holdings.

Despite pressures within the system, despite the loss of deposits, and despite the rise in interest rates, the US banking system has been re-leveraging the economy, not forcing a deleveraging!

Whilst the banking system continues to add leverage to the economy, one of the most fundamental dynamics for recession is not only missing, it is reversed!

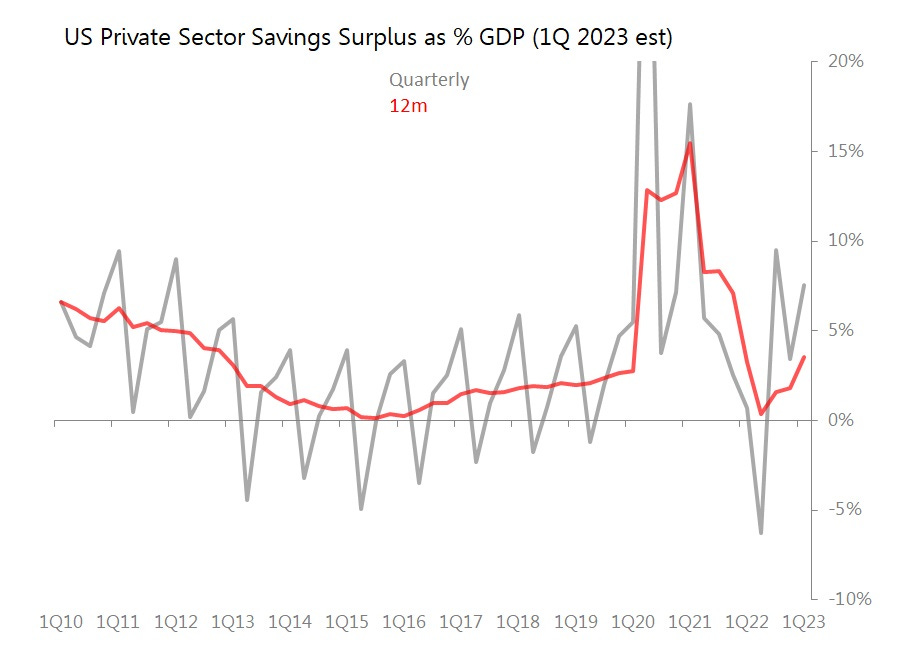

Finally, we can check cashflows by looking at the private sector savings surplus (or deficit). This is calculated by subtracting the fiscal deficit (ie, public sector dissaving) from the current account. For the private sector economy to be under immediate and irresistible pressure, we should expect to see the private sector a) running a savings deficit and b) the banking system unable or unwilling to offer sufficient credit to allow the private sector to maintain its spending patterns regardless.

In this case, the private sector was running a savings surplus of about 1.8% of GDP in 2022, and this has probably risen to around 3.8% of GDP in the 12m to March.

So not only is the banking system allowing/applying more leverage to the economy, but the private sector is already running a savings surplus. Cashflows, then, continue to support an economic expansion.

Conclusion: Although key signals such as return on capital directional indicator and terms of trade may be rolling over, they are doing so only mildly and from a historically elevated position. More, and most surprisingly, these ambivalent but mildly negative signals are offset by the unexpected results from the banking sector and from private cashflows. These show not only that private cashflows remain positive - increasingly so, actually - but that despite rising interest rates and banking sector fragility, there is a mild re-leveraging of the economy underway. These are not the sort of conditions which normally result in recession!