Recession Watch: Investment

Recessions happen when problems in stocks compel a change in flows

When it comes to recessions, we need to think in terms of stocks and flows. Recessions are dramatic changes in flows made unavoidable by unignorable problems in stocks. There are a number of different ‘stocks’ which can develop such problems to make a ‘flow’ response unavoidable. For example, the stock of private credit could become unserviceably large relative to expected income. Or the amount of capital deployed could become far too large to be profitable at current rates of revenue. Or, on a smaller scale, stocks of inventories could prove to be too large, or too small - another situation which will be resolved only by an alteration in flows.

Since the ‘flow’ response is, by definition, embedded in time, interest rates will inevitably play a role in the speed with which stock problems can be dealt with. However, one would expect that the impact of interest rates, and their power to hasten or delay the resolution of the stock problem, rather depends on what sort of stock is causing the problem.

This way of understanding business cycles, and particularly recessions, allows at least two observations.

First, the economic slumps of the pandemic years were not recessions: they were medically-induced economic comas. The language, of ‘recovery’, and any analysis which attempts to force a ‘recession-recovery’ dynamic on what is currently happening, is mistaken at a fundamental level.

Second, because the economic coma ‘reset’ the economic system in a way which may - we don’t know - have recalibrated what is or is not an appropriate level of any number and variety of stocks, an examination of those stock levels is a good place to start.

How likely are recessions now? Let’s look at what we know about various types of stocks. This piece starts with one of the most important stocks: the level of capital stock. Subsequent pieces will attempt a similar judgement on other stock levels: credit, employment, and- though right now I have no idea how to do this - regulatory costs.

In the Dupont Analysis of corporate return on equity, the key metric for capital-intensive companies is usually asset turns (sales/total assets). For major economies, I construct a proxy for asset turns, using final spending on domestic product (ie, GDP ex-inventory movements) as the numerator, and an estimate of capital stock as the denominator. That estimate of capital stock is generated by depreciating all quarterly gross fixed capital formation over a 10-year period . These are done in nominal terms because i) ‘real’ capital stock calculations, although frequently made by people who should and probably do know better, are technically impossible; ii) balance sheet assets are nominal, not ‘real’, and balance sheet pressures will certainly affect corporate investment decisions.

The result is a ‘return on capital directional indicator’ (ROCDI) and it turns out that inflections in that indicator are very good indicators of likely short-term movements in investment spending. When the ROCDI turns up, you can be almost certain that investment spending will accelerate in the near future. Conversely, when the ROCDI turns down, investment spending will slow, but the response time is less predictable - when greed trumps fear, investment spending can continue unchecked even as ROCDI is falling.

So, what is the evidence? In summary, the US is on a knife edge; the Eurozone and Britain look well positioned to avoid recession. Germany and Japan’s current investment spending is not justified by changes in return on capital, which suggests that excessive optimism in both countries is vulnerable to a recession-producing disappointment. China is in retreat, with its underlying dynamic almost unchanged by the pandemic.

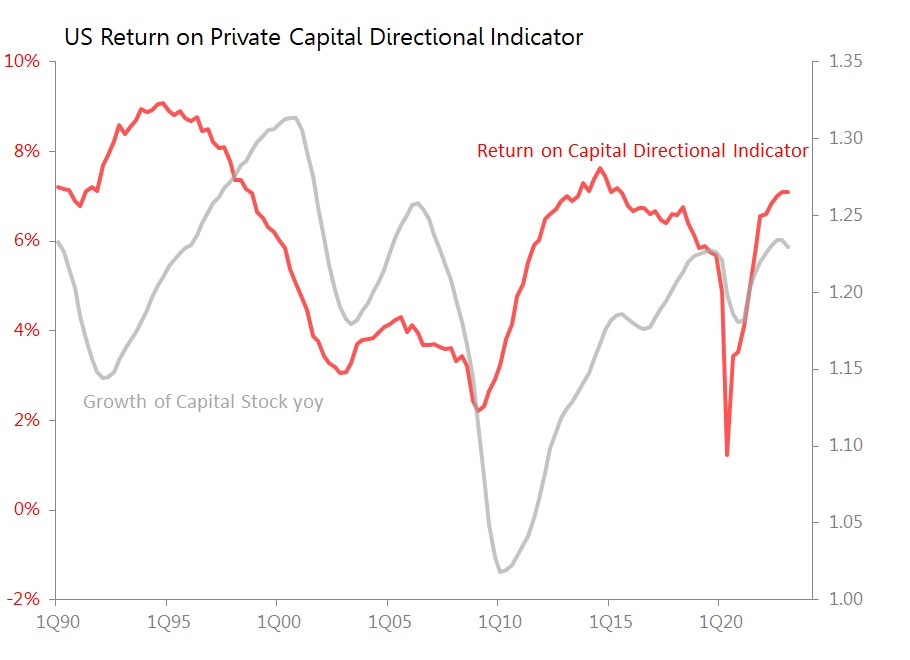

US - On a knife edge

Prior to the pandemic in 2020, the ROCDI had been in mild retreat from the highs seen in 2015. At some point, we should have expected this retreat to have resulted in slowing investment spending, and in fact, this was already beginning to show in the 2H2019. In that sense, the pandemic happened at a ‘useful’ time for the US, bringing forward dynamics already emerging in the economy. So recovery was quick: by mid-2021, the ROCDI had already recovered to pre-pandemic levels, and investment spending accelerated.

By 1Q, however, the ROCDI has seemingly topped out, and investment spending is slowing. The overall level of ROCDI remains at historically high levels, so gives not compelling reason to expect a sustained investment slowdown. Perhaps we are looking at the sort of slowdown seen during 2015-16.

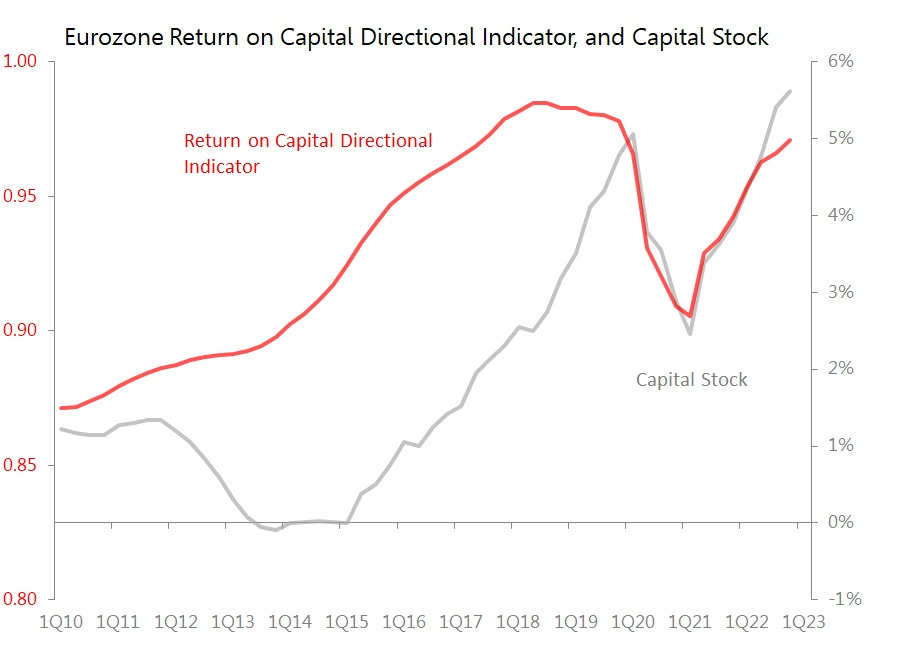

Eurozone - Surprisingly Strong Cyclical Signal

The Eurozone springs a surprise: by end-2022, the ROCDI has almost recovered to pre-pandemic levels, and capital spending has responded vigorously to that upturn. If the Eurozone is to enter recession in 2023, it will not be in response to a capital surplus generating a supply overhang.

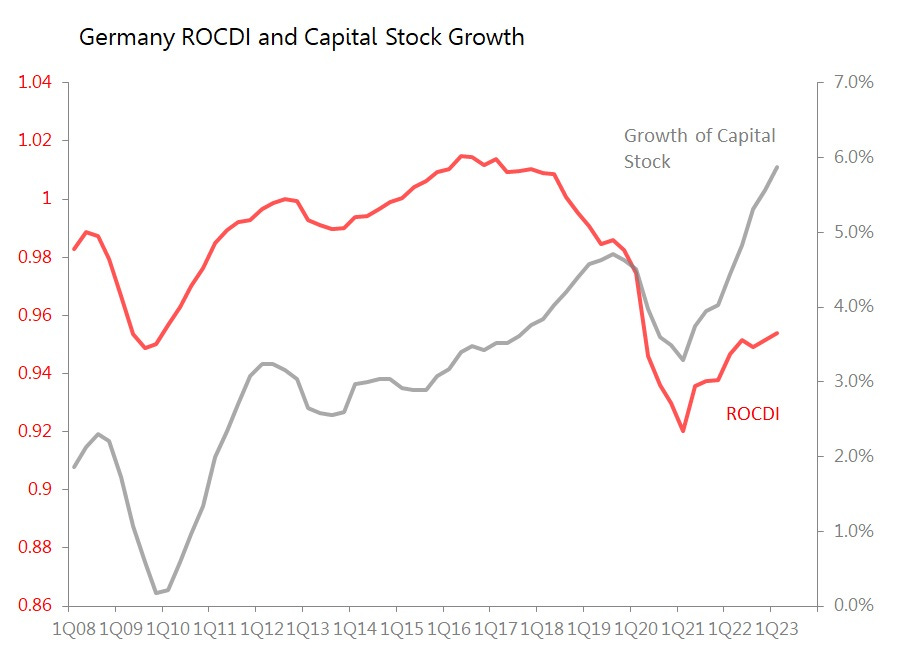

Germany - Vulnerable as Optimism Looks Excessive

Within the Eurozone, however, Germany looks vulnerable. Although the ROCDI is rising, it is doing so only very slowly, and is not in touch with pre-pandemic levels. In addition, rather like the US, Germany’s ROCDI had peaked in 2015, and was already in clear decline through 2019. As with the US, the pandemic will have accelerated and intensified a slowdown which was already on the cards. The problem now is that the surge in investment spending over the least couple of years has been far stronger than is justified by the modest and uncompleted recovery in ROCDI. It is a problem of excessive optimism, of expectations vulnerable to disappintment.

Note, the situation looks a little worse than this. If you include exclude construction investment, ROCDI is not rising, but is rather falling slightly. Either way, the vigour of the investment spending is not currently justified by the return being made on that investment.

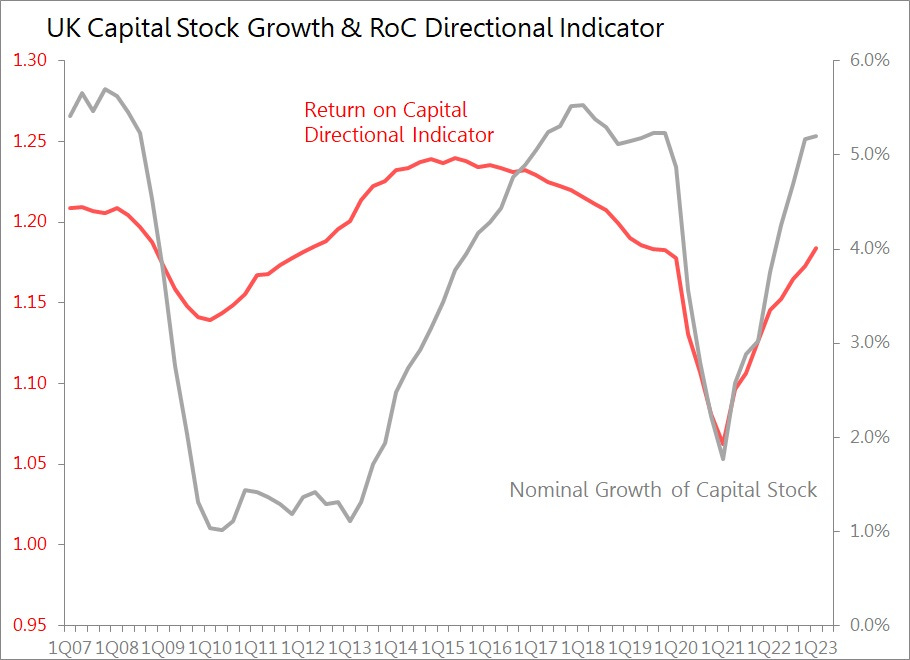

Britain - Surprisingly Healthy

It will come as a considerable surprise to Britons (like myself), but on this metric at least, Britain looks likely to avoid recession, at least as far as investment-spending is concerned. ROCDI has returned to pre-pandemic levels, and continues to climb. The growth of capital stock has already returned to (but not exceeded) pre-pandemic levels, and - at least on its own terms - looks in no danger of needing to fall.

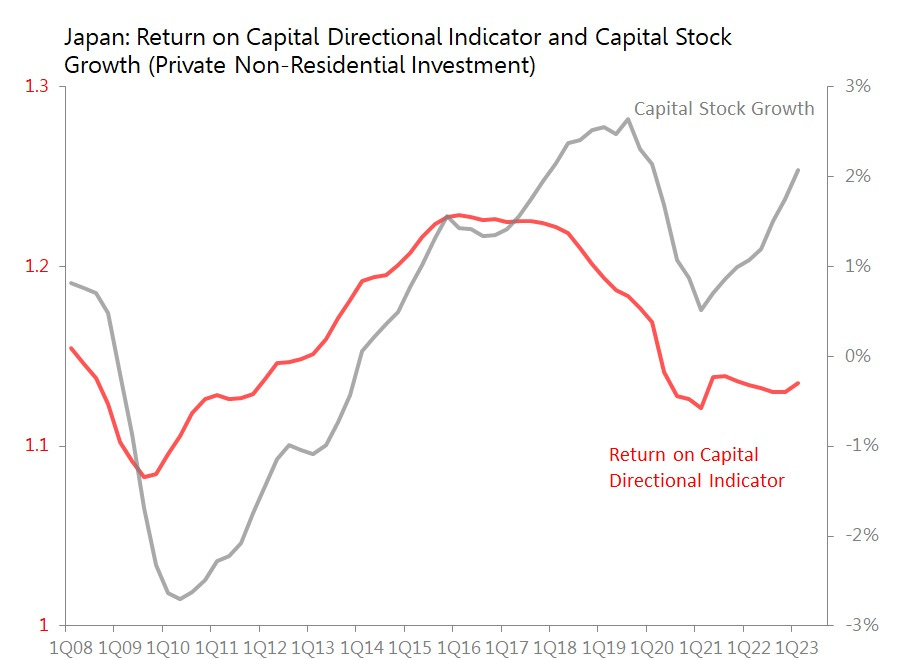

Japan - No Recovery + Excessive Optimism

Japan looks like Germany: there has been almost no recovery from the fall in the ROCDI seen during the pandemic years, and in any case, the falls of 2020-2021 were merely a slightly extension of a longer-term retreat in the ROCDI already underway. However, despite almost no upturn in the ROCDI, growth of capital stock has accelerated sharply during the last five quarters, raising the growth of capital stock back to historically high levels. I therefore suspect that there is a high degree of economic optimism built into current investment spending, which is therefore vulnerable to disappointment. Recession possible.

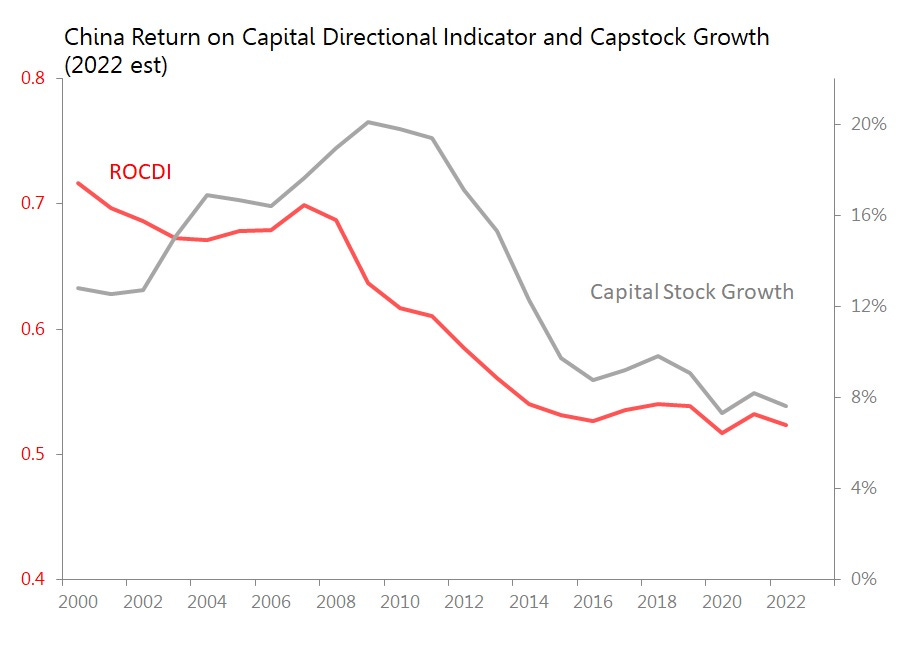

China - The Slow Retreat

China’s national accounts details turn up late and are generally treated with scepticism - although the nominal data used in these calculations is probably less unreliable than the ‘real’ data used in headlines. The chart below includes data up to 2021, and an estimate for 2022 based on partial information. However, the story is clear: China’s ROCDI has been in retreat for years now, and eventually this has slowed the growth of its capital stock dramatically. The pandemic years seemingly changed nothing.