So finally, this is the message, this is the point: right now, the problems Britain faces resemble the woes of the late 1940s; but it also shares the unobserved and ignored strategic strengths which allowed Britain to prosper, unheralded and unexpected, during the subsequent decade of dull orthodoxy. Now as then: Britain’s economic and financial future is far brighter than currently imagined or priced.

Time to recall the preface to Act 1 of Rhyming Times:

Britain was in a mess. It had just suffered a costly and unwanted divorce from its most important trading partners, putting it under extreme financial pressure. Now it was short of allies. Public debt was soaring, and interest rates were the highest in years, and growth was negligible. The stockmarket had been flatlining for years.

But so much needed to be done: infrastructure was crumbling, and more housing was desperately needed. More, supply chains kept buckling, and a government elected on the promise of national reform and rejuvenation was shop-worn, shorn of some its senior leaders and divided on policy.

To make matters even bleaker, the much-loved but aging monarch was ill. Cancer, it turned out.

Rhyming times indeed. There are striking comparisons between the mess Britain endured in the late 1940s and early 1950s and what the country faces now, in the aftermath of an existential financial disaster (2008/09), a Brexit which disrupted its trade relations and disgusted Britain’s establishment, followed hard by a pandemic which for years put Britain’s fiscal, monetary and social policies on a quasi-war footing. That quasi-war state of mind bred a state which seems no longer to want to ‘enable’ the economy, but rather to ‘disable’ it.

The transition from a wartime economy to ‘normality’ is hard, but as we saw in Acts 2 and 3, it can be achieved when extraordinary policies, taken to be helpful, are abandoned and the mere plodding conformity allows compounded small gains to work their mathematical magic.

One of the key, monumental, lessons from the long 1950s is that lavish fiscal and monetary policy are neither necessary nor sufficient to secure lasting growth.

In fact, they distort the economy in ways which eventually degrade growth prospects. And the great force which reveals those distortions, then gradually expunges them, is the resumption of ‘normal’ interest rates.

Higher interest rates compel the return of fundamental economic truths as they flush out the economic, financial, and political distortions which could be entertained only in an exceptionally low interest rate environment.

Pause here to compile your own list of those distortions - it is a target-super-rich environment.

Always bear in mind, however, that interest rates are the price of the future. If interest rates are zero, the message is that there is no consequential future. So what you do now need not take account of future consequences (such as business failure, economic stagnation etc). Bad decisions are not bad decisions, and in corporate life political displacement activity is an easy substitute for the hard hard business of making a business, or an industry, work.

The economic frailties we see now, and the conditions described in Act 1 are obvious enough:

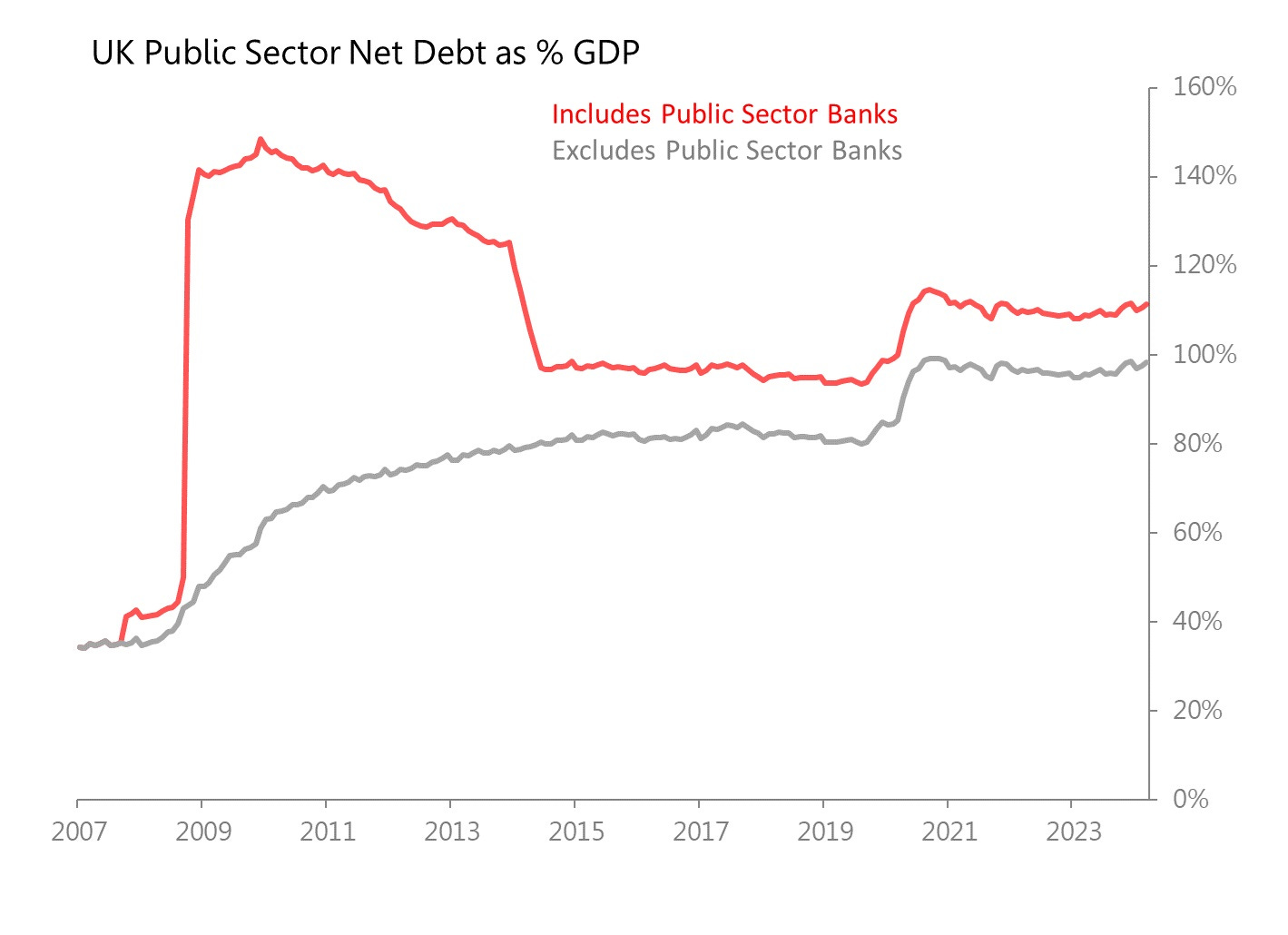

Unusually high levels of public sector debt, either flirting with 100% of GDP, or topping it at around 110% if you include the debts carried by those banks rescued in the financial crisis and yet still in public ownership. Compare that with the c35% levels seen as recently as 2007.

The economy has not registered significant growth for more than 15 years, and has flatlined since the pandemic. In real terms, the economy at the end of 2024 was only 1% bigger than in pre-pandemic 2019. But this pattern of slow growth is not merely pandemic-related: the economy has growth only 15.6% since 2007.

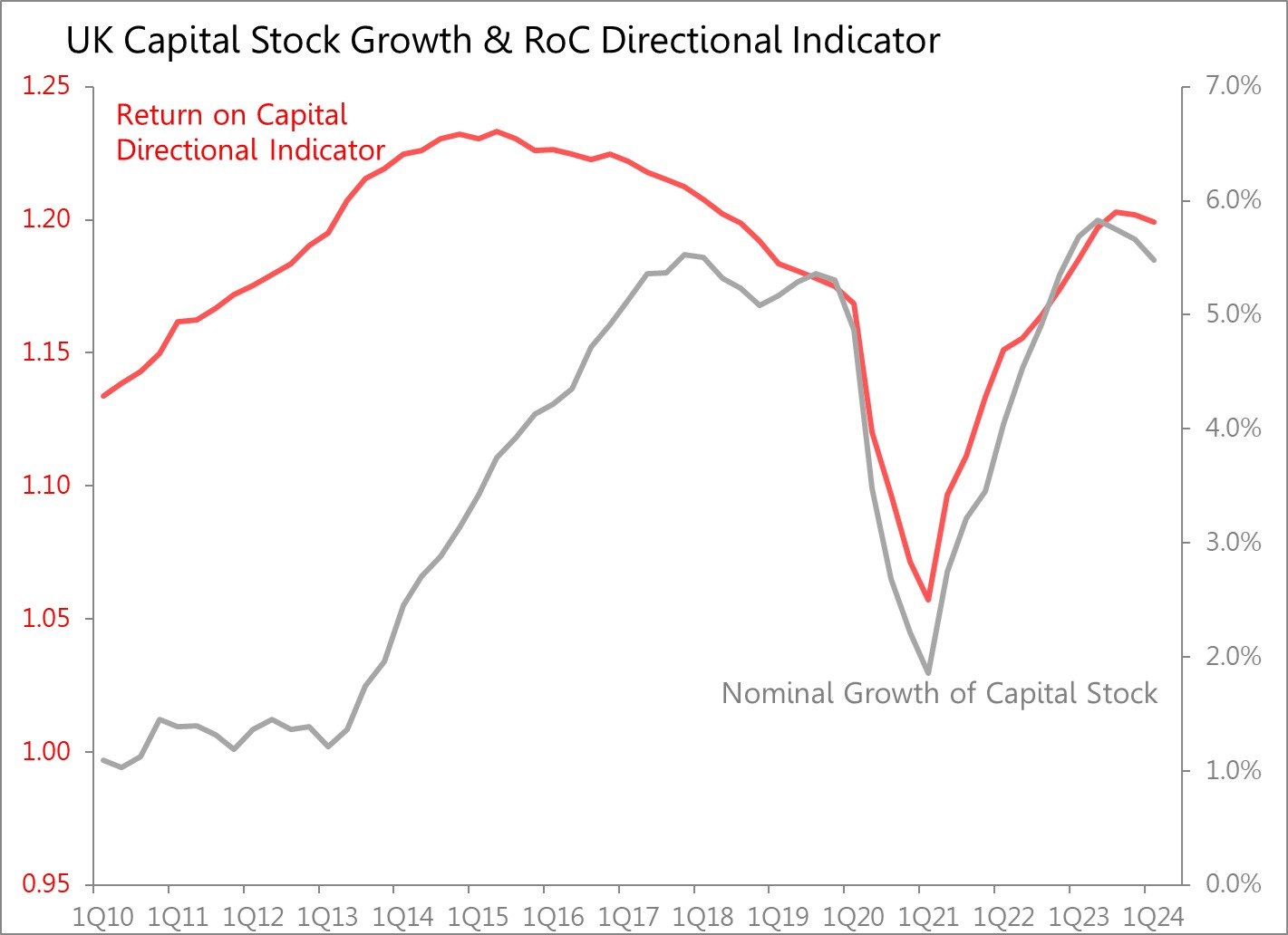

A decade of of declining return on capital, as discovered by my Return on Capital Directional Indicator (ROCDI), disguised in the immediate inflationary aftermath of the ‘war economy’ and now reasserting itself.

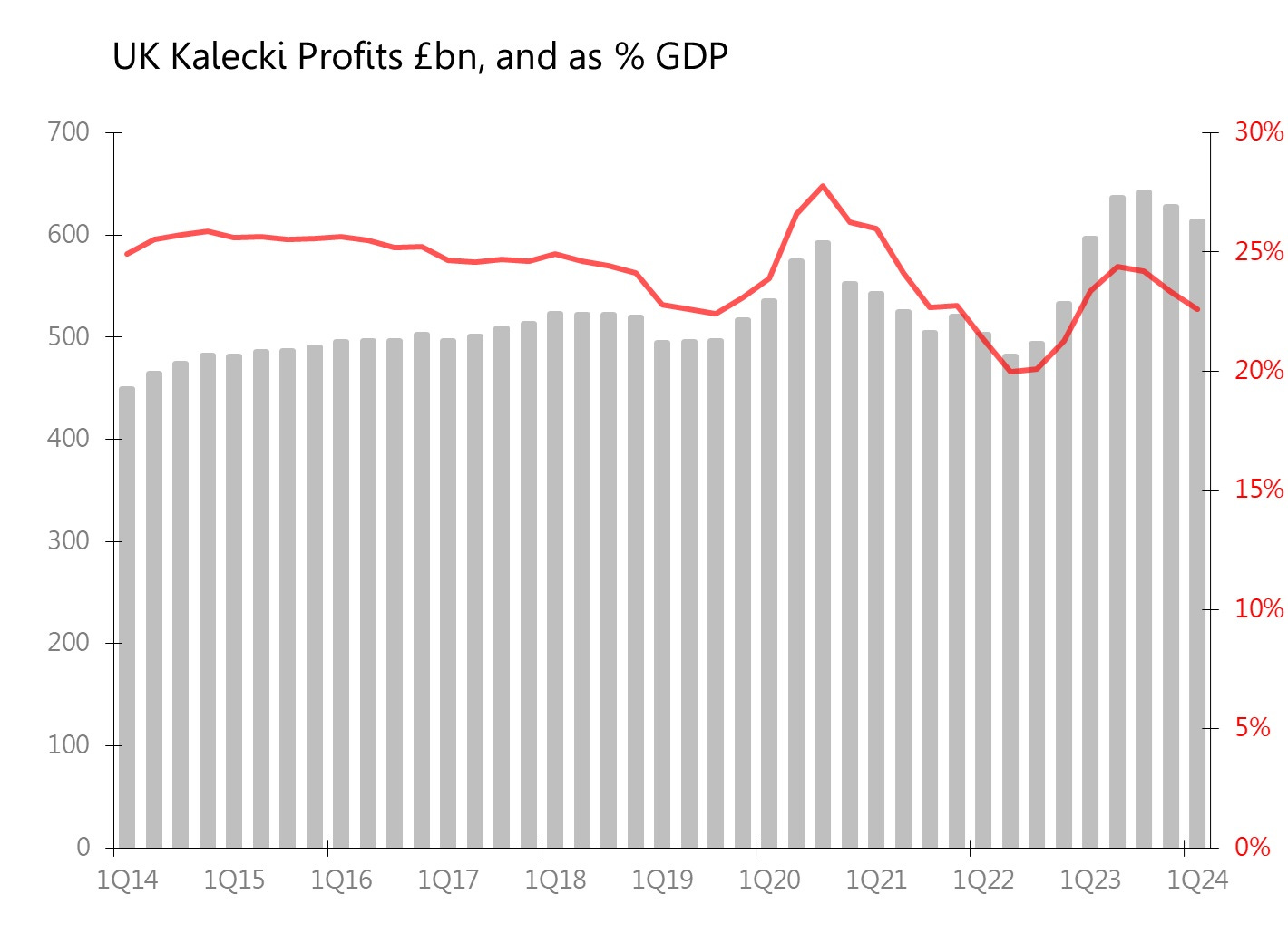

Much the same story surfaces in the calculations of Kalecki profits, which in the 12m to 1Q24 fell 2.2% qoq but rose 2.8% yoy. After the distortions caused by the pandemic years’ embrace of a fiscal war-economy, profits as % of GDP are once again resuming the slow and marginal fall seen throughout the last 10 years. In the 12m to 1Q profits/GDP stood at 22.6%, vs a 10yr average of 24.2%.

A consequence of this extended economic failure is the return of rationing. Rationing is imposed either directly or by ‘dynamic pricing’ regimes, reflecting infrastructural neglect (hose-pipe bans); by commercial neglect (regional communications); by deliberate policy (energy, travel, healthcare, social care), and often an unholy mix of all three.

Other aspects of rationing may simply be generated by the corrupting influence of political parties seeking funding (housing). Britain’s major housing shortage results from extraordinarily low interest rates (demand) and a derisory level of house-building (supply). Between 2010 and 2023, an average of 165k new houses came to market, approximately half the average annual number built in the 1930s, even though the population is much larger and is expanding through unprecedented mass immigration. Making matter worse, many of the those new homes were designed for and sold to foreign investors, rather than the domestic population. As a result, the average selling price of a new build is now 38% higher than the average selling price of an existing home! So London has a housing crisis and yet huge numbers of vacant (unaffordable) properties.

And, of course, the FTSE 100 index has flatlined for at least the last decade, and the stockmarket no longer functions as a significant means of raising capital.

The far better, and unrecognized, news is that Britain now also shares some of the characteristics which underpinned the success of the ‘long 1950s’, described in Act 3.

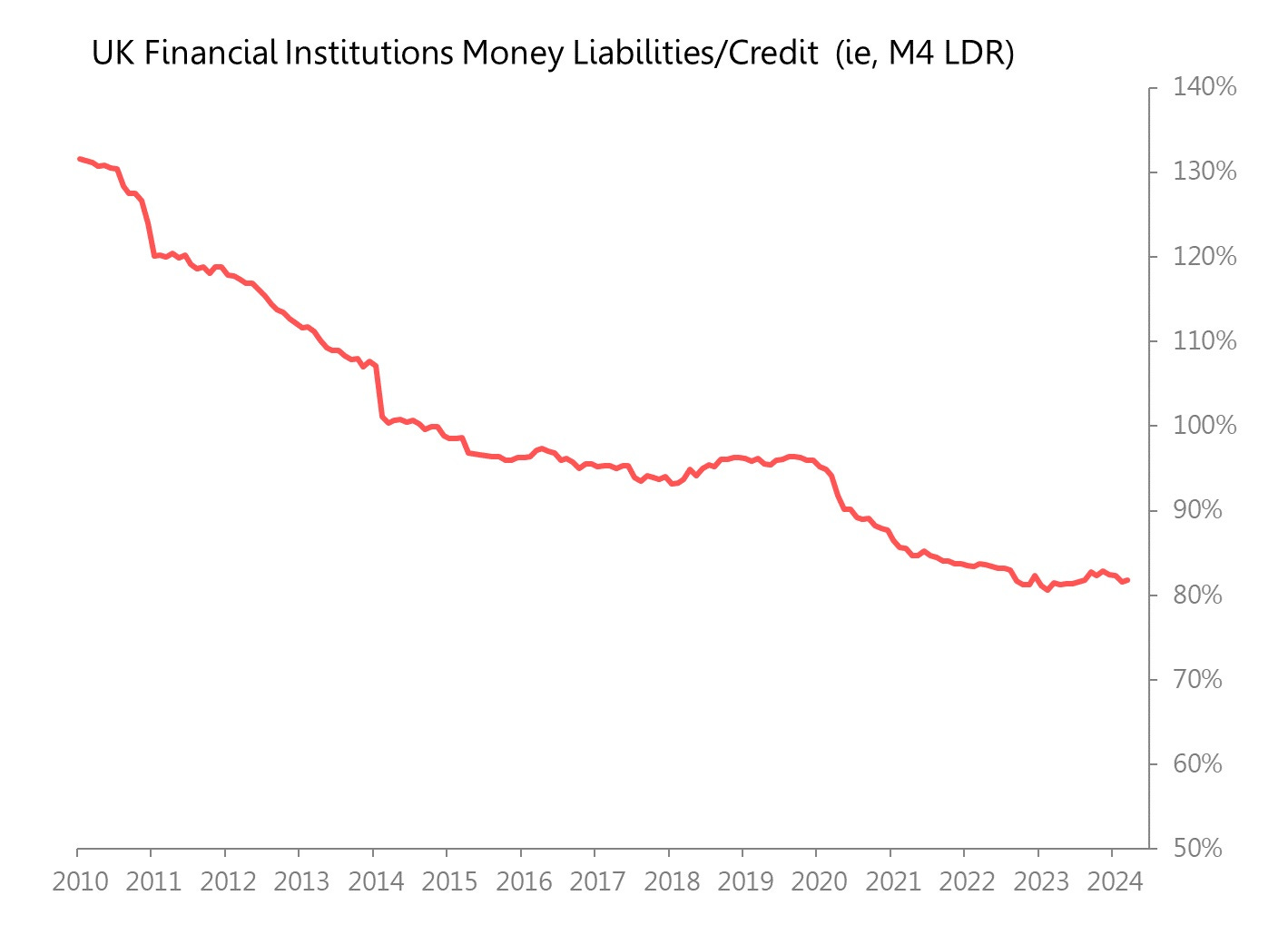

Although there is plenty of attention paid to the rise in Britain’s public sector debt, the fact is that it has been accompanied by, and in part directly contributed to, a massive deleveraging of Britain’s private sector and its financial system.

Britain does not have a debt problem. Rather, Britain’s private sector, and the financial sector has deleveraged to what are now historically extreme levels.

Taking the Bank of England’s widest measure of money liabilities (M4) and aggregate credit, the M4 Liabilities/Credit ratio has fallen to around 80% only, down from 2009 levels which stood at near 140%. (For comparison, consider the Eurozone’s M3 Deposits / Credit ratio, currently at 158%).

The financial system’s deleveraging is, of course, the mirror image of the deleveraging of the broader private sector. Households’ net position with financial institutions currently stands at a net deposit of £258bn. Consider that as recently as 2010, by the same calculation, households were carrying net debt £300bn. The deleveraging continues apace, with households growing their net deposit base by £40bn during the last six months. Never in recent British financial history have household balance sheets been in such good shape. Though strange and unremarked, these are the numbers!

The recovery of household finances has been accomplished in three phases: the first being a response forced by the financial crisis of 2008/09; the second arrived with the pandemic quasi-war economy, in which the government dished out huge furlough payments whilst at the same time forbidding people to leave their homes - an inadvertent debt jubilee; a third wave is currently under way, probably inspired both by higher interest rates and also a rise in precautionary saving.

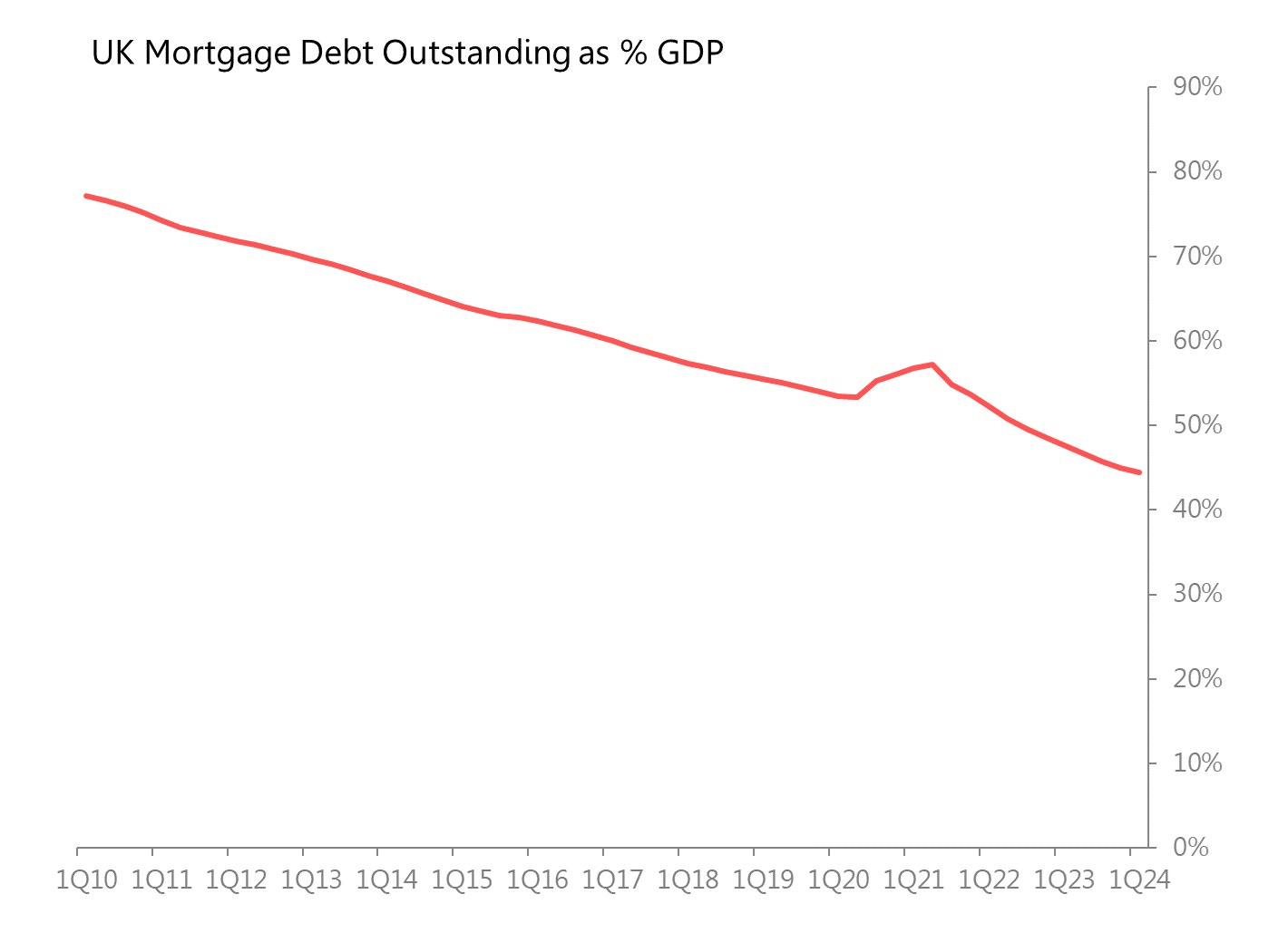

Despite the disastrous spiral in Britain’s house prices, mortgage debt / GDP ratio has fallen dramatically, from damage done by Britain’s dysfunctional housing market, from 77% in 2010 to 44% now.

Private companies have undertaken a very similar deleveraging, transforming from a net debts of £360bn in 2008 to net deposits of around £200bn currently.

Just as in the long 1950s, the private sector continues to shore up its position through sustained modest savings surpluses. In turn this continues to grow deposits at the historically underleveraged financial institutions. And since those financial institutions now find themselves having to pay interest on those deposits, the commercial imperative lend grows with the deposits.

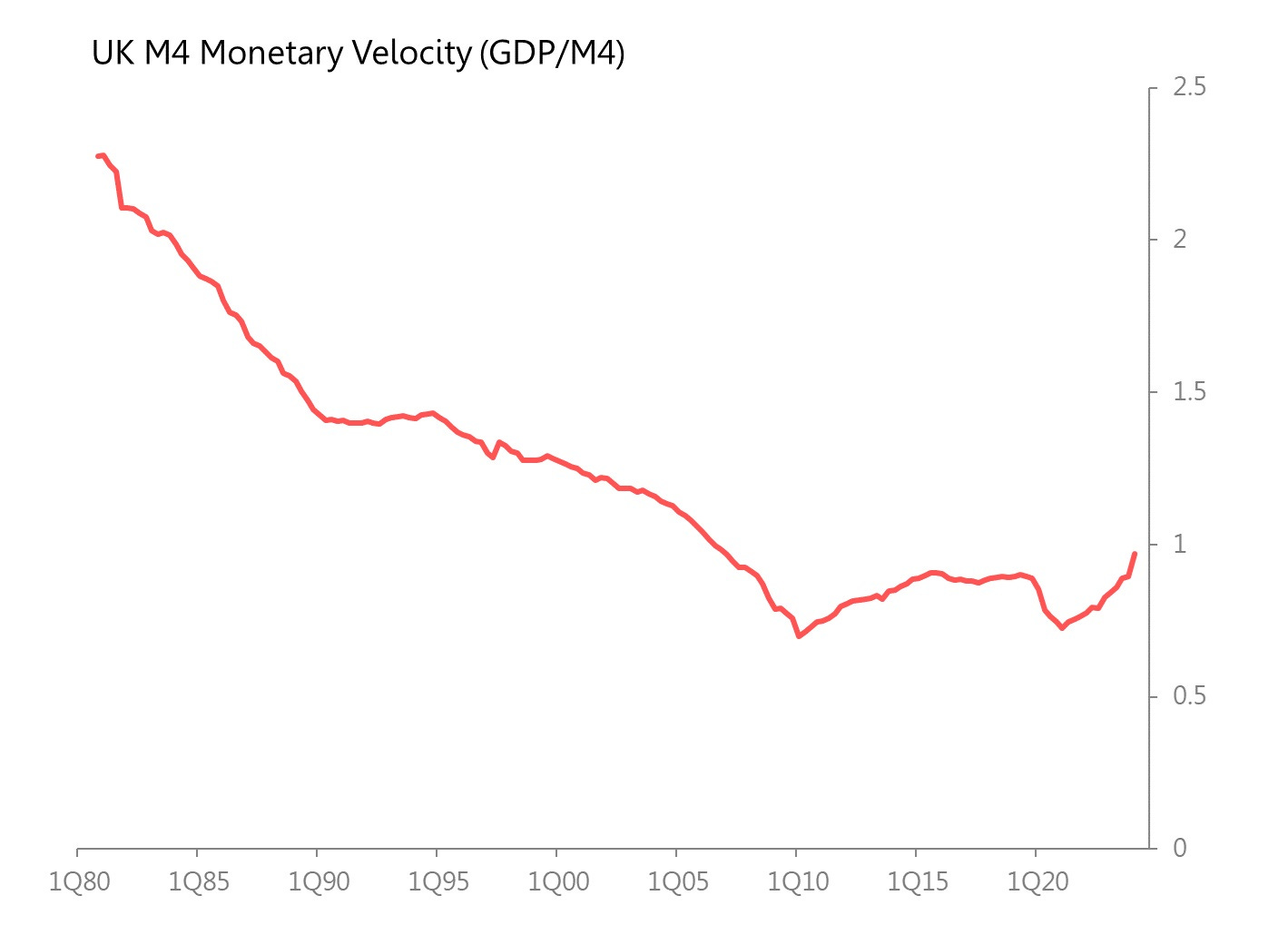

This brings us to the key point: that the modern-day long collapse in monetary velocity, seen also prior to the long-1950s, is likely to be reaching its nadir. Monetary velocity is defined here as GDP/M4, and it fell from 2.27x in 1980 to 0.71x in 2020. As the emergency measures accompanying the financial crisis were moderated, it recovered to around 0.9 between 2015 and 2019. The return to emergency monetary accommodation during the panic slashed it back down to 0.72 in 2020.

The recovery from that appears now to be happening, with velocity returning to 0.97x in the 12m to 1Q24. This is the highest velocity recorded since 2006!

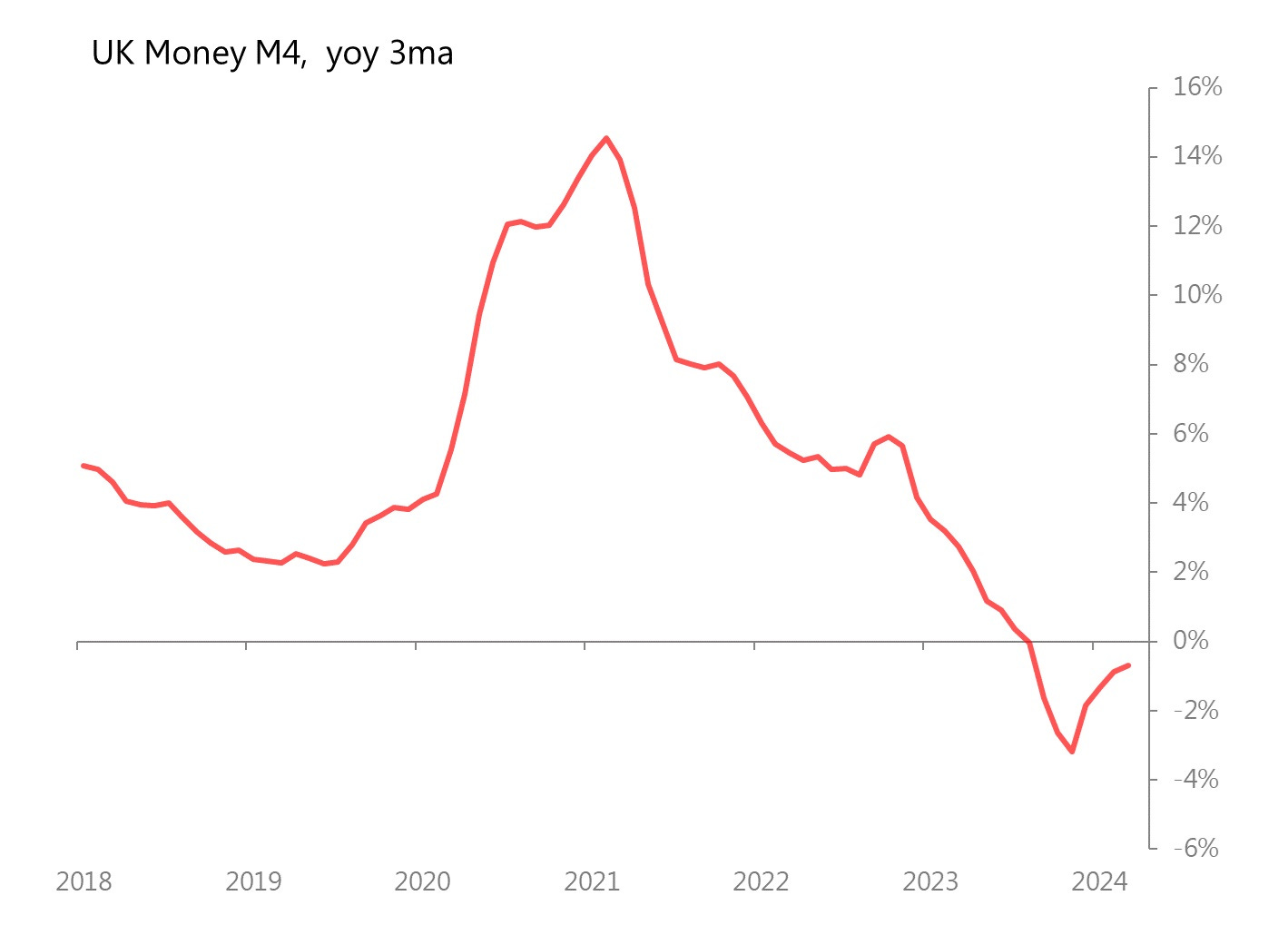

We saw in Act 3, how during the long 1950s the sustained rise in Britain’s monetary velocity offset and in the end over-rode monetary policies which were kept unobtrusively orthodox throughout the period. Similarly, right now, the most recent rise in monetary velocity is the result of nominal GDP growth 6.2% in the 12m to 1Q, whilst M4 money was falling 0.7% yoy.

And this is the argument. If:

i) monetary velocity has indeed already reached as low as it can go,

ii) the net flow of deposits from the private sector continues to put pressure on Britain’s underleveraged banks to lend or invest;

iii) this in turn makes continue monetary contraction probably impossible to maintain;

then the maths compels us to expect a sustained rise in nominal GDP growth. No extraordinary fiscal or ‘accommodative’ monetary policy responses are necessary or helpful in this process. Rather, what is needed is an understanding - seemingly forgotten by both policymakers and commentators - that sustained modest gains in GDP growth will transform an economy’s fortunes over time.

Just this situation has been seen before during the long 1950s. We can and should expect something similar to emerge and transform Britain’s economy, and stockmarket, over the coming decade. Britain’s in a mess: the opportunities are unrecognized and immense.

But can we discover likely the engines of this growth? Yes, with ease. The only difficulty is choosing which to highlight. But here are two. First, a surge in house-building is not only desperately needed, but would by itself be sufficient to unleash growth directly (through building and equipping houses). But the second-order impact on growth is probably larger, with the liberation of the idle economic and social energies of a generation currently unable to start their own homes. A major house-building program would be sufficient by itself to power a decade (or more) of sharply accelerated growth.

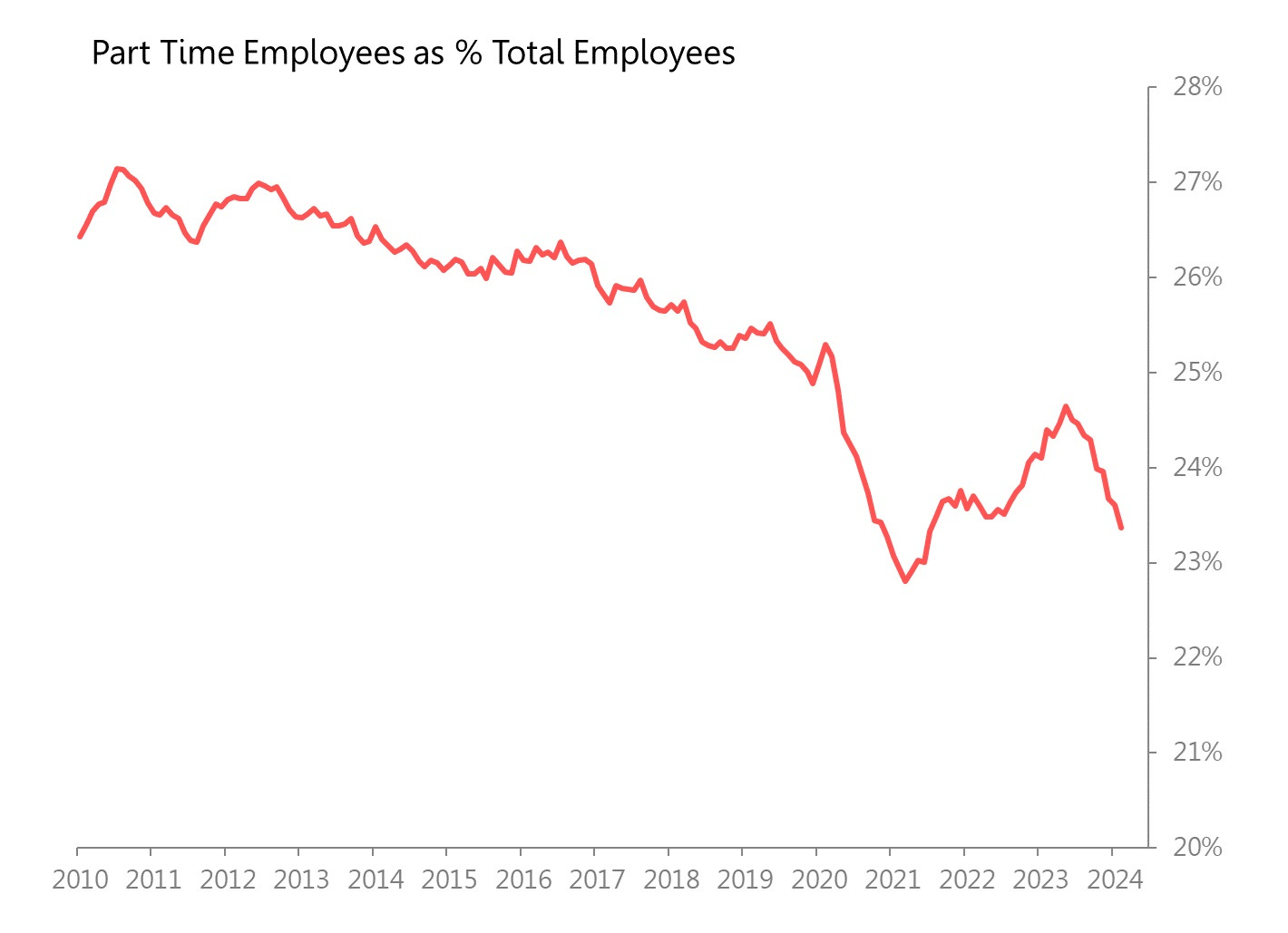

Second, ‘normalized’ fiscal and monetary policies are likely to discourage part-time and self-employment whilst encouraging full-time employee employment. By itself the move from part-time to full-time work would necessarily increase output per employee, and most likely raise GDP per capita. Happily, this trend is already visible, with the latest data showing the number of part-time employees falling 302k yoy whilst the number of full time employees rising 270k. The net impact on production of a 270k rise in full-time employees is, of course, more than enough to offset lost production from the 302k fall in part timers. Again, a continuation of this trend is not necessary, but certainly sufficient, to raise output per worker.

Victims? Yes, ‘normal’ fiscal and monetary policies will inevitably wreck bad policies, and the companies which require them to survive. Tough - they are distortions arising during a decade and more of economic failure. Their survival is not necessary for a prosperous ‘long 2020s’. Their eradication probably is.